I came across a few interviews with Carmen Strungaru as I was browsing the web for articles about emotions in the animal world. It didn’t take me long to find out more about this extraordinary woman who is an ethologist and a researcher, a biologist, author, translator and lecturer. Just who I should talk to about emotions and… emoții [emotions]. Warning: the following interview is music to my ears so I hope it will change your perception about nature and wildlife.

This is how Mrs. Carmen Strungaru introduced herself before answering my many questions:

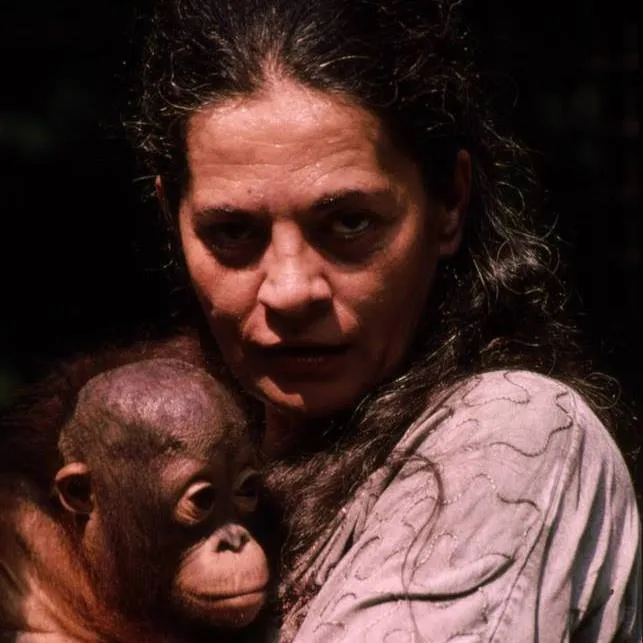

I was born in 1952 and I have always wanted to know “everything” about human and animal behaviour. I taught Animal Ethology and Human Ethology at the University of Bucharest, Faculty of Biology, between 1991 and 2018 and briefly at the Faculty of Psychology. I participated in numerous specialty conferences and conventions in Europe and North America, I was a visiting professor in Indonesia and Japan, I travelled twice to the Trobriand Archipelago in Papua-New Guinea and to Indonesia (the islands of Java, Kalimantan, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Moluce, Bali, and Lombok).

Once retired, I started to translate the works of prominent ethologists/biologists such as Frans de Waal, Antonio Damasio, Edward O. Wilson, Mario Livio, Alexis Willett and Jennifer Barnett, Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman, Martin Seligman, Frances Jensen, William Calvin, David Reich, Michael Spitzer, Nick Lane, a.s.o

I have managed to learn quite a few things regarding human and animal behaviour.

I fell in love with nature when I was 40 years old. You were much younger when you fell under its charm, I guess. Do you remember how it happened?

I did not “fall”, but I had a close encounter: my love had four tentacles and came to me slowly, gliding from under a fence onto the cobblestone pavement that bordered a long line of brick houses. It was so mesmerizing, I am still under the spell of the animal kingdom. I had read a lot of books and treaties on nature; however, my first trip to the mountains took place when I was 16 and I first set foot in a village at 24, when it became clear I was more at ease around the wild animals in a zoo (where I went weekly) than with the cows that rang their bells and stopped in front of their gate at dusk. Could I blame the “chance” of living in “the big city” or my hyperactive imagination fuelled by the books and a few documentaries I could access? Could I blame my nature? It’s hard to say.

Papua New Guinea, 1995, was your first ever scientific trip. 30 years later you got the chance to re-read your diary and turn that adventure into a book. Tell us what it was like to see Papua New Guinea again through the eyes of a more experienced person.

It might sound supernatural, but the minute I recovered my diary and cracked it open, I realized I knew it word for word, as if I had written it the day before, and my overall feeling was that I had just returned from the trip. The only thing that has changed, though, is the way I now perceive the woman I was 30 years ago. As I was reading, I was scolding myself: “Oh, you were so naive, you must have looked so outlandish to the natives”. Or: “How could you wish and attempt to change those children who were playing with a balloon fish or those youngsters who were trying to catch a dog so as to trade it for cigarettes?” I believe that this nagging is proof that I have changed over time, that this adventure has determined me to perceive things and people with a bit less of that learned European stiffness, that it has turned me into a more human human being.

You have always dreamt of exploring Africa. You have done so much research, you’ve gathered a lot of expertise in an area few have ventured to understand and yet, nobody wanted to support this endeavour of yours. How is this possible?

Ha, ha, ha! How many people do you think would be willing to sponsor a middle-aged woman, mother of three, who wants to travel to Africa because it has been her childhood dream? Wrong place, wrong time. Maybe, if I lived in another country or in a different time, I could stand a chance… When my time came, it was already too late, the map had changed. Africa is still within me and honestly, I am not sure the picture I hold of it would match reality. What I know for sure is that it matched the reality of Papua New Guinea and of the Indonesian islands.

You have been working on a new book, “Ethology for dummies”. When are you planning to launch it? And how would you describe Ethology in a sentence? I first encountered the term last year, when I was reading for emoții, and that’s when I learnt it is a science.

To avoid any academical description, I could tell you that Ethology is like an assessment of life through the perspective of the 5Ws (and a few more questions). The book you mentioned,Homo Vanus – Our Daily Dose of Ethology Although it is based on a dense bibliography, the book is not a university lecture. Animal behaviour, just like the human one, is intriguing and prompting for those who are willing to look around or within themselves, regardless of their age, education or occupation, hence the subtitle – Our Daily Dose of Ethology. At the same time, Ethology is uncomfortable, it forces us not only to praise our cultural side but also to consider our biological component, which is hard to accept even for the Homo Vanus (conceited man) of the present.

Nevertheless, I believe that real science shouldn’t also be “too serious” and that a pinch of humour won’t harm; on the contrary, it can facilitate understanding many topics.

While I was doing research for my photo album I realized there is very little information about animal emotions. Aside from a few books (especially those of Frans de Waal that you translated) the internet has not helped much. What do Romanians think of Ethology? Is it attractive, is it acknowledged?

It happens almost every single time: whenever an ethologist starts talking about animal or human behaviour, the audience rolls their eyes and mumbles “Well, but that’s common sense, so what’s the big deal?”. Once you ask the audience to elaborate on that “big deal”, the answers range anywhere between facts, beliefs, cultural stereotypes and “It’s their habit” / “It’s our habit” (and these are the most numerous statements).

What Romanians think about Ethology, that I couldn’t really tell. Most of them, I guess, don’t even know it is a science and they couldn’t care less. It was first taught in Bucharest in 1992 at the University. I started teaching it from scratch but the students loved the course so it became more and more popular. Nowadays it is taught in several university centres and I hope the number increases because it is a necessary science, not only for the help of future biologists and psychologists, but also for doctors, vets, sociologists, and many more.

You used to be a Lecturer at the Faculty of Biology, University of Bucharest. How did your students perceive Ethology? What are your best memories from those years? Are there any stories you would like to share? Do you have a successor in this field?

Ethology was perceived as I mentioned before. However, the step from “what’s the big deal” to understanding the intricate mechanisms that are the foundation of behaviours, how they are interconnected or how they contend with the cultural component, that is, indeed, galvanizing. Memories, there are plenty: from trips we took together, on our own, throughout the country to spending my free time with them at my holiday home in the Danube Delta… What I cherished the most were my lectures. I knew what time they started but no one could tell when we’ll call it a day. Sometimes we decided to have a break, passed the hat around to buy some bread, cheese, tarama and whatever else we could afford and continued our talks (we were allowed to speak with our mouths full) until the guard urged us to leave the building. So, you see, there is a real connection between Ethology and bread…

I taught alone, I had no assistant; unfortunately it was impossible to open another position, although many of my students would have raised to the occasion. It’s all right, they were so good they were offered jobs abroad, as they were worthy! Now my course is taught by my dear former student, Mrs. Livia Petrescu, and she is doing great although (or in spite of the fact that) these lectures demand a lot of stamina and they lack, almost entirely, any formal support. There is still the need for an assistant to cope with all the issues of the job such as supervising some solid undergraduate and post-graduate dissertations/theses or setting up some serious research projects, to name just a few. When you’re on your own, all you can do is stick to the syllabus and try to get over the fact that no one and nothing can help you push things a little further.

Is Ethology able to make us love and respect animals more than we do? Do you have a secret for that?

Primum non nocere (First, do no harm) should be the commandment that guides any being gifted with reason, conscience and intelligence – as we pretend to be. Yet, the mere fact that the axiom is still, to this day, associated with healthcare personnel, is testament of how homo-centric we are. It could also explain why we are so radically against the idea that the other animals could be also gifted with even the slightest sign of reasoning, conscience or intelligence.

As long as we continue to believe we are superior to the rest of the animal world, there is no real chance, I think, to change the way we relate to them. I wouldn’t suggest we should love them; that would be too much. We should, at least, respect the speck of life that animates each and every one of them. Changing this perception might come from the children who are “educated”: to educate the adults around them.

Besides the intelligence of a chimpanzee, a raven or an elephant, that I knew about, I also noticed and felt that animals show their emotions: they look after their offspring, they have courting rituals, they show loyalty, fear, pain, they demonstrate adaptability or patience (polar bears in Churchill, Canada, for instance, can wait for months for the bay to freeze over so that they can go ice-hunting). I have also read about how whales whisper to their calves in order to stay under the radar. Do we need more examples so as to conclude that animals have feelings and their emotions are similar to ours?

Emotions can be either sublime, superior, divine, creative and inspirational or, on the contrary, something we should eliminate or get rid of so as to show off how grand we, the humans, are. It’s high time we decided whether these emotions are good for us or they’re bad for us.

What we hate most about emotions is that they can affect our reasoning, control and consciousness, those very features we like to consider, just like language, exclusive human traits. Which leads to a paradox that has been (and still is) fuelled by the scientific world: on the one hand, when contrasted with conscience and reasoning, emotions are regarded as inferior, primal, animal. On the other hand, when scientists mention emotions, they often deny their presence in the animal world or at least they aim to emphasize there is fear and there is “real” fear, there’s joy and there’s “genuine” joy (where real and genuine are, they claim, for people only).

To sum up, scientists have been using a lot of concepts but never managed to establish which is the one and only theory that would explain emotions; is it the adaptative evolutionist theory, the physiological theory, the neurological or the cognitive one? What they missed is so obvious: emotions have a physiological foundation that is peripheric and central, neurological, cognitive and they also have an adaptative role. The false excuse is none other than that “similar to ours”.

The irony of it all is that we have been taking pills that are supposed to calm us down, ease depression and relieve stress and we also lack the decency to acknowledge that these drugs and their efficiency have been established as a result of… tests performed on animals.

I read somewhere that shame is typical only to humans and yet, on many occasions, I saw cats or dogs hiding in a corner, head down, after they did something bad. Could it actually be fear, not shame? Are scientists still afraid to discuss animal emotions?

I don’t know if what we call “shame” in the animal world is equivalent to the same concept we, humans, use. The core of it is, mainly, the fear of punishment (be it physical, psychological or social).

Nowadays, anyone, anywhere is able to get a photo or a video of wildlife. Do you think technology has changed the way we perceive animals?

I am certain it has, for those who choose to observe and to process what they see. Anything from being able to snap details that would be hardly noticed otherwise to capturing interactions, is captivating and touching. This is the great asset of a talented photographer or videographer: being able to record what is touching in an objective manner, being able to pass the emotion felt by the observer when taking the photo on to the people who admire it. There’s also the opposite situation: it depends on whoever the audience is and how sensitive they are to some images that were definitely staged so as to force an emotional reaction.

In the process that opened my heart to nature and wildlife I also looked at myself with new eyes. I saw how much the flora and the fauna are in distress and it dawned on me that the humans are suffering, too. There were 20 degrees outside last Christmas; extreme weather is not a rare occurrence anymore. Therefore I learnt that by striving to help nature and wildlife, I am also fighting to secure myself a better life. What have the animals taught you?

They taught me to be modest, frail and tenacious. They taught me about attachment. They taught me many things, it’s hard to pick one. I could fill one page, at least, with the precious lessons they have given me.

You have accumulated a lot of experience and expertise, so what should we all do to preserve what we have, to look after nature?

We should be more modest, tenacious and attached, on top of being more reasonable (which should be our default feature, right?).

My La NORD de cuvinte trips have showed me that wherever money rules, climate change is not an issue for the government or the citizens. Have you noticed this in your travels?

Well, my trips happened long before these changes became obvious, so no. Nevertheless, I am fully aware of how blind and insensitive people can be even when money is not involved. I moved to the countryside 12 years ago and I noticed people are carelessly burning toxic waste in their backyards, that only a handful of us collect, sort and recycle our garbage (although the services are free of charge). Unfortunately, here, a good farmer is the one who sweeps up all the dried leaves and then burns them (a spotless garden should have no leaves on the ground, you know) and then, when spring comes, generously spreads fertilizer around every tomato or bell pepper seedling. Sewer tanks are stealthily emptied towards neighbouring plots or into the village river (whose banks are full of junk and rubbish, a horrific sight). I know a village is just one village, but when this happens in every village… People don’t understand that their actions have consequences and whoever has tried to lecture them on sustainability has been ridiculed (“Look at these city slickers, they came here to teach us farming, ha-ha”).

In the last six months we haven’t had any serious rain at all. The land is dry, the wells have dried up. It looks like we’re about to have to leave this place to look for water elsewhere. And everywhere around, people say: “It’s God’s will, we can’t fight it”. Isn’t it interesting how we always praise but also blame it all on the divinity?

Every parent tries to teach their offspring to love and respect this big house, our planet Earth. You’re a mother of three; have you managed to hand this down to your daughters?

I have never tried to teach them to love and respect nature. They grew up in a house with two biologists where there was always some animal, big or small, in a corner or under the table. When they were toddlers, we had to mind our every step on the sidewalk for fear we’d step on an ant. They made me give CPR to a dead bee (stiff and dry) and there, I must confess, I cheated a little bit: I gave it mouth-to-mouth until I blew it into a bush. When my daughters grew older, our house became a shelter for stray kittens and puppies, little sparrows or pigeons, a squirrel, snails, frogs, you name it. At some point we hosted – simultaneously – a three-legged dog, a one-legged owl and a pigeon whose leg had been operated on; one small in-house Orthopedy clinic. We never do harm: any fly/bug/spider that might come into our house leaves it alive and in one piece; a twig found broken outdoors is brought in, put in a vase with some water and, most of the time, it sprouts roots and gets moved outside, in one of the many pots. Two of my daughters are “fundamentalist” vegetarians and the third has just purchased a house near Cluj just because the fir trees in the garden shelter an owl colony (of around 30 members). Naturally, they pass all these principles on to my grandchildren. What I did teach my daughters was that every being is entitled to life and that animals can never be described using terms like good/bad or harmless/harmful.

I usually ask a few “fill-the-gaps” questions when we reach the end of the interview. If you were an animal, you would be a...?

Rat. This would be the least I could do to thank rats for everything they have taught me. I would also like to convince myself I understand them almost entirely.

I know you have had the opportunity to get through emoții. Is there any photograph you like more than the others?

To a specialist, the album seems to lack extensive scientific facts. To anyone expecting to find “the most amazing shots”, frantically flicking through the pages (the way some browse the internet), the photos lack that kind of “wow factor”. To an iPhone owner, the fact that one bird is flying from left to right, another one from right to left and two other birds are resting on a branch is definitely not “the thing”; they are sure they could take 20 such photos in less than an hour. To any wildlife enthusiast, the pictures in this album lack that pleasing quality that cannot be described but would make them cry out “Aww, look how sweet this is!”. To an environmentalist, they would be disappointingly mild compared to what the reality of animal life is. To a painter, most of the photographs would be examples of the grisaille.

Why should you take time and enjoy this album? First, because it is available and you came across it. Once you have removed the plastic wrap and you touched its cover, you can feel the texture and smell the odour reminiscent of old prints. Even before you look at any photo inside, you’ll rejoice in the thickness of the quality paper which could only reproduce exquisite images. Then, the title sums up all these first impressions – it’s all about emotions.

Alas, we have all been victims of emotional manipulation for quite some time, so we don’t judge a book (only) by its cover, right?

How do I appreciate this album? Just like I enjoy a good piano concert, when I am still pleasantly surprised besides the well-known sequence of notes. There’s volume in the photographs, there is a certain atmosphere. It is as if you could feel the breeze or, on the contrary, the dry, frosty air; and that stillness is a bit eerie. It could be a selection of frames from a story with a complicated plot that I have only partial access to and, as a result, I need to fill the remaining gaps myself. There is nothing demonstrative about it, nothing provocative. It exudes calm and also a certain amount of sadness here and there, unexplained but present. I am sure these photographs are the result of long feverish waiting (frigidly feverish, I dare say) with a lot of patience on both sides of the camera. Next to one of the photos I like a lot there’s this text: “When Mother Nature is giving a performance and you’ve got first row tickets, you think the world is perfect. I felt the same way watching this seagull flying around, as gentle as a lullaby. Up there in the skies where it glides carried by the wind, everything is flawless: there is no trouble, no disappointment and no sorrow.” The world seen through Rareș Beșliu’s eyes is somehow sad but it is at least as good as the one seen by the seagull. The pictures featuring egrets, pure white against the white background, are very stylish; so are the cormorants. And a special Kudos to the groundhog! The texts are well balanced and sensible, pairing the photographs really well.

Let me tell you one more time: I am impressed by the subtle mix of ingredients in this album that manages to get right to the viewer’s heart without being ostentatious in any way.

And now, to end on a positive note, let’s allow ourselves to daydream for a while: you can choose any photo in this album and get into it, see what it’s like to be there. Which image would that be?

“…we don’t need to look in the same direction as long as we trust each other […] you’re my second pair of eyes and I am yours.”

Thank you very much.

Let me thank you for this album – it has been a pleasure. I really hope everything you do in the future you do it with grace, sensibility and an open heart.